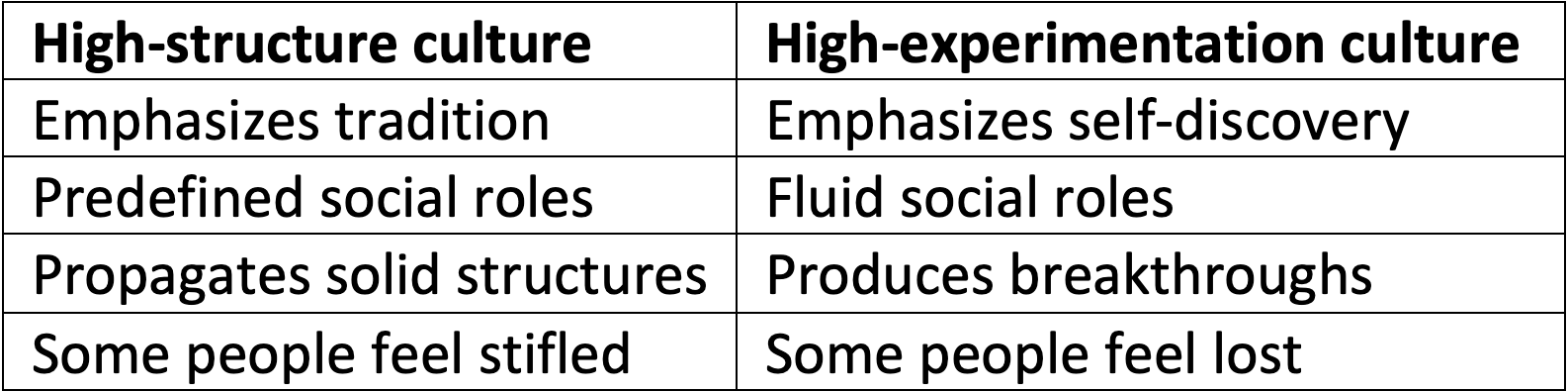

I’ve been thinking recently about high-structure vs high-experimentation cultures and what it means for intergenerational cultural transmission.

Examples of high-structure cultures include groups like the Mormons who provide a very structured and detailed life plan to their children. Young men go on their missions, come back, get married, and start families almost immediately with women of a similar age, having several children by their mid-20s in many cases. They receive extensive support from their parents and church, with a clear path laid out for them at every step. Starting a family in your early 20s is hard, but the clear plan and support structure makes it somewhat easier. The network of memes in this culture isn’t amazing, and it can be downright terrible if you don’t fit the mold, but works well enough for most people who grow up with it that they’re able to do a decent job of tightly replicating it on down through the generations, and church membership is still growing at a significant rate. The Mormon meme network is great at producing more Mormons as well as keeping the Mormon meme network intact from generation to generation. However, this sort of system is very intolerant of people pursuing different paths if those paths conflict with their assigned roles, and many young people end up fleeing this environment when the structure and their individual preferences become uncomfortably incompatible. In fact, a recent survey found that 36% of people born Mormon had left the church, which means that it isn’t just LGBTQ people leaving, it’s a significant chunk of the people who start in the system. Note that leaving the church is a huge deal – you basically lose your entire social network – so people don’t take the decision lightly. [Note: since publishing this, a couple of friends have pointed out that the Mormons have more experimentation than I give them credit for; there’s openness to integrating aspects of other cultures as part of the worldwide mission, as well as a doctrine of direct revelation, which allows church leaders and even individuals to receive “updates” from God.]

High-structure cultures don’t have to be religious. A child being groomed by their parents to one day take over the family business also falls in this category, as does a child who is pushed to become a chess prodigy by their grandmaster parents.

San Francisco culture (especially SF startup / tech culture) is an example of high-experimentation culture. Teens are encouraged to consider alternatives to college and start companies early in their careers. Journeys of self-discovery and self-transformation, as well as periods of extended travel, are encouraged. Failure is accepted and even celebrated. There’s a common trope that most mature institutions are corrupt and broken and should be disrupted. People explore nontraditional relationships, new types of living arrangements and social organization, and new forms of art and gatherings. Some of these experiments succeed and become new mainstream technologies and cultural norms, while many fail. Sometimes after trying many alternatives, people discover that the tried-and-true method of doing something is actually pretty good for them after all. All this experimentation also comes at a cost. Outcomes for people in a high-experimentation culture are widely variable, with some getting exactly the life they want and others flaming out repeatedly or flailing for years and feeling lost. People tend to have kids much later if at all, as it often takes a long time to converge on the right approach to life if you’re experimenting through a period of extended adolescence.

Society as a whole benefits from having both high-experimentation and high-structure subcultures. The high-experimentation subcultures produce a bounty of technological, cultural, and social innovations, with the successful ones spreading across the society. Meanwhile, the high-structure subcultures predictably produce a reliable group of people that keeps core functionality and structures running. The two are inherently in tension, but together they can drive a lot of progress if the groups communicate and don’t get too extreme.

I personally have been drawn to a high-experimentation culture my whole life, and it has worked out well for me in that I have been able to craft a life that I’m generally very happy with that would not have been possible under higher-structure cultures. However, I can’t say for sure whether it would have worked out this well in almost all other timelines or if I just got lucky in this one; the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Also, it took me a long time to get the components of that life right, so I’m having kids on the late side. I believe that our high-experimentation culture needs to be capable of being transmitted to the next generation, and that means making it compatible with having a family. Kids are expensive from both a time and a money perspective, and that means there’s less room for experimentation both leading up to having them and afterwards.

There are some changes that could make it easier to have kids under a high-experimentation culture. High quality state-run childcare, as is common in Nordic countries, can significantly lower the time and financial cost of having kids. Cohousing-with-kids arrangements also allow multiple families to share in child-raising time and expenses. Construction-friendly housing policies make housing less forbiddingly expensive, making it easier for families to afford to have enough room for everyone. Cultural change away from helicopter parenting can reduce the time burden of raising kids. Solving the problem of cost disease in universities can make the prospect of paying for college education for multiple kids less daunting. In South Korea, which has the lowest birthrate in the developed world (0.92 births/woman pre-pandemic, now 0.84), almost 20% of women cited education costs as their reason for not having another child.

As I think about the next generation, I wonder whether it’s possible to have the benefits of both high-structure and high-experimentation cultures, keeping the parts of the structure that are already close to optimal and experimenting with the ones that aren’t. The trick is that at the age of, say, 20, it’s hard to tell which structures are holding society together and which structures are just generational cruft or an oligarchy of profit-takers standing in the way of progress. I think there’s a way to teach history that could help new adults entering the world make better guesses about which is which.

A lot of history class is teaching granular facts such as particular historical figures, cities, nations, famous inventions, and wars. This is of course interesting and helps establish a historical narrative for society, but is less useful when envisioning how society could and should change in the future.

Instead, I think it could be more helpful to teach the history behind everyday life and the underpinnings of society so kids understand how the current “normal life” came about, and why it came to be chosen over alternatives. Why do cities exist? Why do suburbs exist? Why do most people live in single-family homes or apartments? Why do we use money? Why are some things expensive and other things cheap? Why do people get married? Why is private life organized around families? Why do Americans eat the food they do? Why do kids go to school? How did America standardize around cars for transport? How do we get information about the state of the world, and who pays for it? Why do certain groups face discrimination? It’s also important to understand failed social experiments and how different cultures around the world have approached the same problems.

I recently ran across a book, “The rise and fall of American growth”, that does a great job of charting how everyday American life changed from 1870 to 1970, and it answers a lot of questions of why the America I was born into looked the way it did. The book is long and dense, but the information within it is important as each successive generation contemplates the future of America, and the material could be packaged in a way that’s accessible to kids.

Knowing the history of why all these aspects of society came about and the complex interdependent systems they’re embedded in is important if you want to change them. Circumstances change over time, and knowing the reasons why something is the way it is can help predict the consequences of changing it.