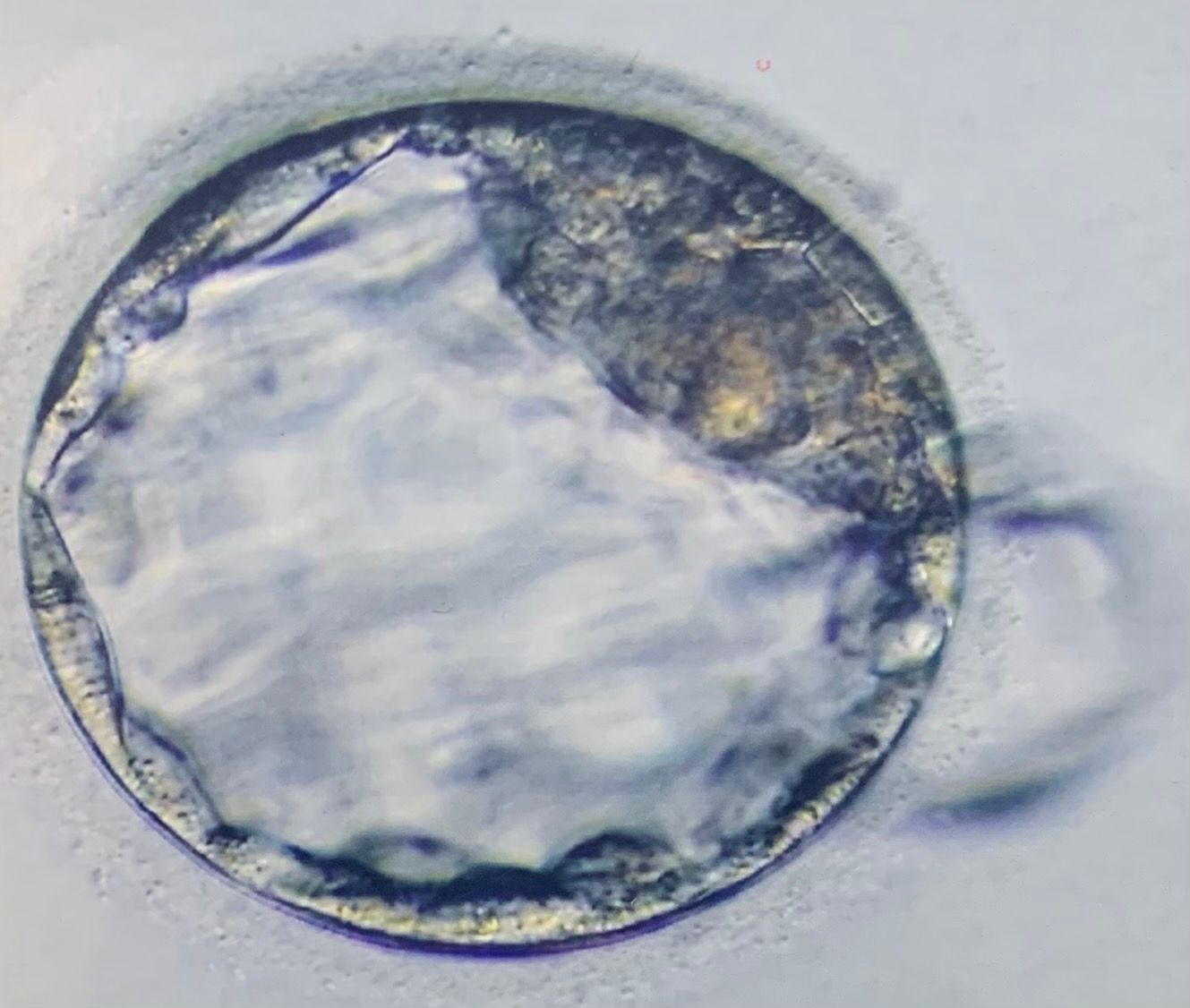

We’re making a little human! The photo above is one of the eight frozen embryos we’ve had in storage since 2019. The pandemic delayed us for a while, but now we’re back on. This particular embryo is currently burrowed inside the uterine lining and is busy establishing its blood supply. If this one doesn’t work out, and there’s about a 15% chance of that at this point, then we have seven more. As a side note, we’re working with a surrogate to bring the baby to term, so if you see Helen without a baby bump at a party in 6 months, don’t worry; everything’s probably OK.

I think as IVF becomes more common it’s going to do some very interesting things to how we view human life. Here’s why:

People are made, not just born

For most of human history, pregnancy was a magical process that began with the ecstasy of sex and ended with the delivery of a live human into the world. Before the human popped out and took its first breath it was an enigma growing inside the mother.

Technologies such as fetal ultrasound and amniocentesis have started to give us the ability to peer inside the womb and get an early peek at this mystery, starting a few months after conception. However, with IVF and genetic screening of embryos, we start to see a lot of what happens at and immediately after the conception stage.

The conception stage is particularly alien to our notions of identity and humanity. An infant cannot talk but it already has a distinct personality, and it’s ready to absorb all the love, attention, knowledge, and milk it can. More importantly, it looks like a human. It’s very, very easy to emotionally bond with a little human; we have millions of years of biological programming to make that happen.

However, an embryo looks and feels much more like a delicate biological-nanotechnological clockwork mechanism, a self-unfolding blueprint for a possible human life if a mother chooses to gestate it. Additionally, with IVF you usually don’t just have one embryo, you have a set of them. You also know things about them. Some are in better physical shape than others, some have chromosomal abnormalities. Some are XX, some are XY. With very recent advances in preimplantation genetic diagnosis, you can screen the embryos for a range of common genetic diseases. This makes the time after conception a very deliberate and analytical decision of which blueprint you want to take on the task of gestating. Embryos are precious, but not in the same way that babies are precious. Embryos are precious because you feel an instant deep respect for their fantastic complexity and latent potential, balanced with a sense of delicateness and the fact that it took a lot of time, money, and pain to extract them. However, I feel far less emotional attachment to any one of these embryos than what I will almost certainly feel toward my child once they’re crawling around in the world.

Ultimately, people are made, not born. A baby won’t develop into an adult member of society capable of complex thought unless someone spends years teaching it how to think, speak, and interact with the world. Similarly, an IVF embryo won’t turn into a baby unless a mother makes the conscious choice to gestate it to term, a process that involves her body not just sustaining the embryo's life, but also flipping a wide range of epigenetic switches to prepare it for the world it’s being born into.

Having embryo selection be a deliberative process adds so much color and thought to the beginning of life that it has significantly shifted me towards this worldview of “humans are made, not born”.

A lot of potential lives are lost, and that's OK

Another thing you learn from IVF is that there’s a lot of messiness and embryo loss at the beginning of pregnancy that’s normally hidden from view. We’re used to each individual human life as being particularly precious and thinking of the loss of a human life as a deep tragedy, but that’s not how it feels at the embryo stage.

The process of creating an embryo often results in a serious flaw, either a morphological issue or a duplicated or deleted chromosome that could produce serious birth defects or a non-viable pregnancy. A sizable fraction of embryos are in this situation, especially for older parents. In normal pregnancies, the mother’s uterus will usually detect that something is abnormal about the new embryo and flush it out, preventing the mother’s body from wasting a pregnancy on a non-viable embryo. Parents can lose an embryo this way in the first few days and not even know. There are a lot of very early miscarriages of this sort that pass unnoticed, and about half of these miscarriages happen due to genetic issues with the embryo.

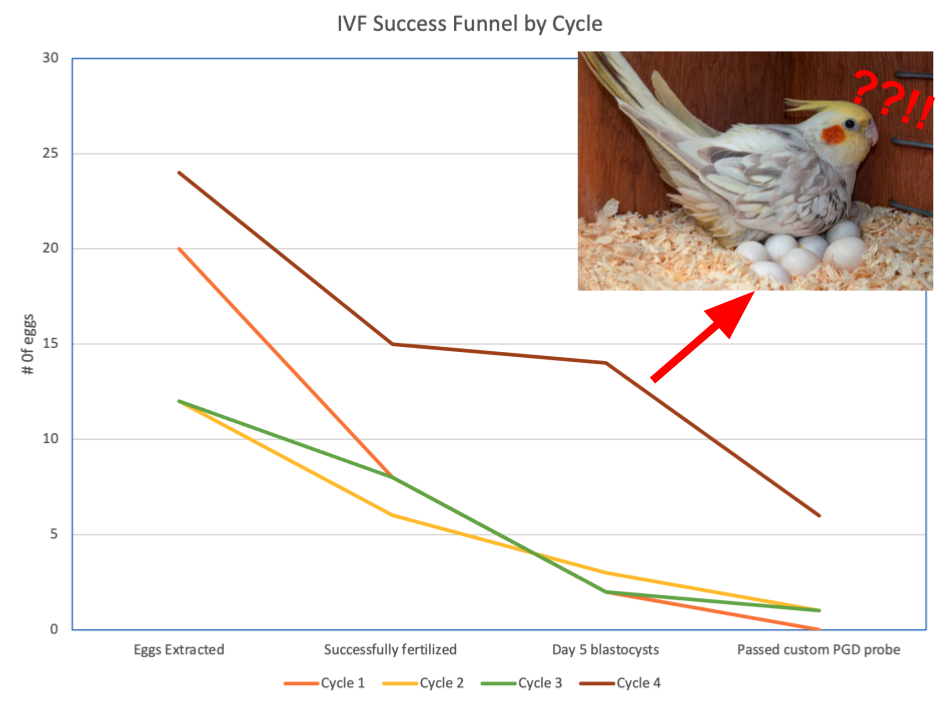

In IVF, it’s all in plain view. The survival rate in this “success funnel” is lower than it would be in the womb as scientists haven’t perfected the art of keeping a growing and dividing embryo alive in a petri dish at the level that matches the human uterus.

In our case, we also had a lot of dropoff at the final stage (custom preimplantation genetic diagnosis probe) as we weren’t just doing the normal screening for trisomies and deleted chromosomes, but were also doing some specific genetic tests.

However, the picture is clear – you start with a lot of eggs and end with relatively few genetically normal developing blastocysts. There’s a lot of embryo loss along the way. Normally your body takes care of that for you, but with IVF you get to watch every step of the process. Watching whole groups of embryos perish at each stage definitely puts you in a mindset of individual lives not being precious until they’ve been gestating in the womb for a couple of months.

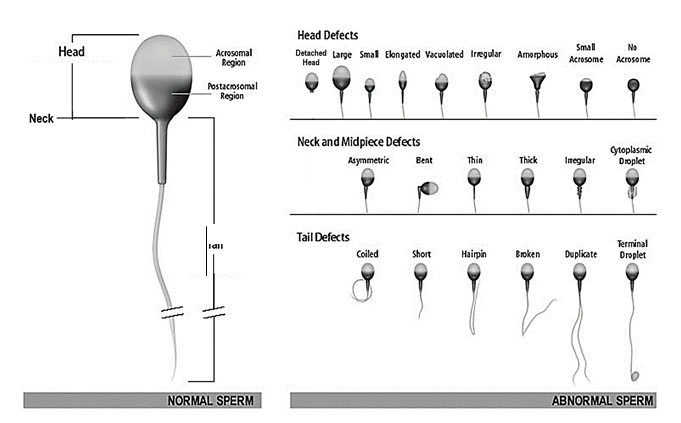

Even further up the funnel, it’s interesting to learn about the extreme non-preciousness of sperm. Did you know that for a typical man, 90-96% of his sperm are defective? By defective, I’m talking about multiple tails, broken tails, misshapen bodies, deformed heads, missing heads, and other issues. The testicles are shady high-throughput factories pumping out vast amounts of subpar product that only occasionally works.

When I got my semen analysis back and saw “86% have morphological abnormalities” I had a bit of a sinking sensation, but the doctor quickly explained, “no, your sperm are excellent!” Given this unfortunate quality control, the vagina and uterus have evolved to act as a deadly gauntlet for the sperm, weeding out the weak and broken ones with a severe test of physical prowess and endurance. During IVF, they need to create a comparable system, so the sperm are often placed in a centrifuge and forced to swim up a chemical gradient. Alternately, in some cases the sperm are hand-inspected individually for morphology, strength, and vigor before being inserted into the egg.

New ceremonies, new traditions

IVF is too new to have developed a set of cultural traditions around it, but it’s ripe for it, as each step is deeply imbued with meaning. It’s the sort of thing that if it were practiced by some remote tribe in the Amazon, anthropologists would write about it in lush detail in National Geographic articles.

It would go something like this: “It starts with a period of induced quiescence for the woman’s ovaries, a time of calm and reflection. Then, with a dramatic ceremonial injection of special hormones, the ovaries roar to life. In fact, they’re brought to such a state of heightened fertility well beyond what is experienced in the ordinary world that each ovary produces several eggs, often bringing the total number of eggs to over 20. Then, the ritual shifts to a temple of science, where the woman and man bring their reproductive material to be wedded and blessed by the priests and priestesses of medicine. The woman’s eggs are carefully extracted and inspected for worthiness, while the man’s sperm are put through a gauntlet of challenges to prove their virtue, with only a few deemed worthy to enter. The priests and priestesses unite the best pairs of sperm and eggs in special ritual pools of water. Once these unique pairings have been made, the newly christened embryos are placed into sealed caves of darkness to develop, shielded even from the eyes of the priests and priestesses. After several days, the entrances to the caves are opened, and the developing embryos are brought out again to be seen by an oracle, who peers into their DNA and gets an omen of what the future holds for each of them. Finally, the man and the woman are brought back in and are shown this clutch of tiny embryos, each a potential human life, and they are faced with the weighty task of choosing which ones to bring into existence.”

We’re not there yet though. Embryos don’t have an annual celebration of conceptionday or implantationday but they do eventually get a birthday if they last long enough. There aren’t celebrations at the beginning of each IVF round or “congratulations on your clutch of new embryos” cards. There is a glimmer of it though – on egg extraction day I still remember the phlebotomist handing me the sperm-collection container with a serious, weighty look and saying “best wishes to you and your family”.

For ourselves, we planned a small ceremony on the first day of IVF injections, and we were lucky enough to be at a party that had a photobooth all set up:

Humans are egg-layers!

I’ve learned that humans hatch from eggs! We evolved from egg-laying animals and transitioned to live birth many millions of years ago, but the vestigial stage of developing inside an eggshell never disappeared, it just moved back in time, inside the womb. Human embryos hatch on around day 5 or 6 of development, and the process is actually quite dramatic and impressive for a clump of cells that has no visible means of locomotion.

The next step is just as fascinating. I always thought babies developed on the wall of the uterus, but no, they burrow inside the wall of the uterus to get better access to the maternal blood supply. In fact, the embryo and mother enter into a tug of war, where the embryo tries to vascularize as aggressively as possible, and the mother limits the extent of the vascularization.

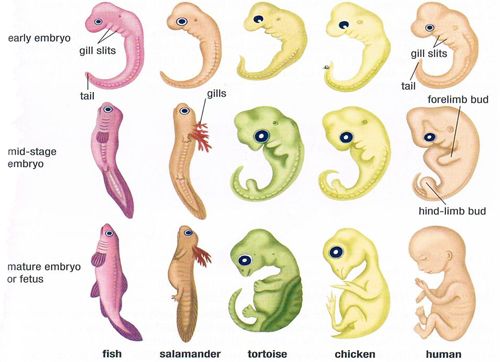

Over the next few weeks, the embryo will hopefully grow rapidly and start to map out a body plan, first establishing a head and a tail, then creating a neural tube, then starting to create organs and limbs. It's fascinating to look at how similar early development is across species. Nature figured out a way of bootstrapping a body layout with toolkit genes, and then made relatively few modifications to these first steps, instead adding additional later steps to direct development into the final form for each species. As a result, early body layouts look similar whether the embryo is a fish, frog, mouse, or human. Differentiation into something recognizably human doesn't happen until a couple of months in.

The blueprint for a human gradually becomes something in the shape of an actual human.

After its time in the lab, our embryo is now behind the veil, nestled in the uterine lining, too small to be seen in an ultrasound. We won't get a peek at it again for a while, and if everything goes well, it should be well on its way to taking on a human form by the time we do! We're looking forward to this next phase of our lives and continuing the unbroken chain of dividing cells that stretches back billions of years to the first life on Earth!